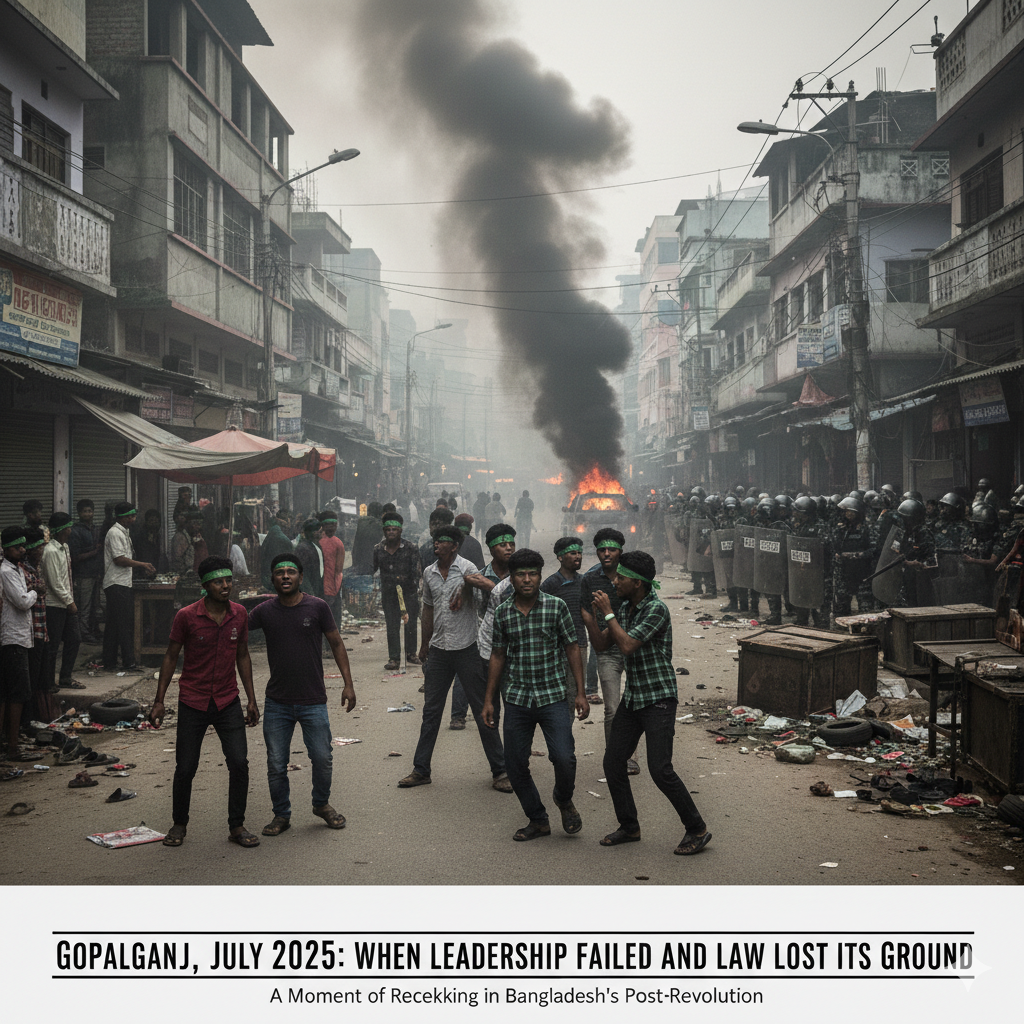

Gopalganj, July 2025: When Leadership Failed and Law Lost Its Ground

On 16–17 July 2025, the town of Gopalganj in southern Bangladesh became the stage for one of the most troubling episodes in the country’s post-revolution period. What began as a political march ended in deadly violence, leaving several people killed, many injured, and an entire district placed under curfew.

For international observers, this incident was not just another clash in a politically restless country. It was a clear signal that Bangladesh’s interim leadership was struggling to translate revolutionary ideals into basic governance.

Why Gopalganj Mattered

Gopalganj is not an ordinary location. It carries deep historical and emotional significance and has long been associated with the political legacy of the Awami League, the party that was removed from power during the July Revolution.

When the newly formed National Citizens Party (NCP) chose this town for a high-profile rally, tension was predictable. In politically sensitive societies, symbolism matters — and symbols, when mishandled, can ignite conflict.

This was a moment that required restraint, foresight, and strong neutral policing.

Instead, the situation was allowed to drift toward confrontation.

From Rally to Violence

As rival groups gathered, clashes broke out between supporters of the former ruling party, participants of the NCP march, and security forces. Roads were blocked, property was damaged, and violence escalated rapidly. Law enforcement appeared reactive rather than prepared.

By the time order was restored, lives had already been lost.

The government’s response was a sweeping curfew — effective in stopping further unrest, but deeply revealing. Curfews are not signs of strength. They are signs that the state has lost control before it could act.

The Leadership Question

Muhammad Yunus, a globally respected figure and Nobel laureate, leads Bangladesh’s interim administration. His appointment raised hopes internationally — hopes for calm, fairness, and institutional discipline after years of authoritarian governance.

Gopalganj tested those expectations.

After the violence, official statements condemned the unrest and blamed supporters of the former regime. But for many observers, this response missed the point. Leadership is not measured by statements after tragedy; it is measured by what is prevented beforehand.

The failure here was not only about who threw stones or set fires. It was about why the state allowed a known flashpoint to spiral without sufficient safeguards.

Questions remain unanswered:

- Why were early warning signs ignored?

- Why was impartial security not visibly established?

- Why did the government rely on force after violence instead of prevention before it?

A Wider Pattern

The Gopalganj clashes were not an isolated incident. They reflect a broader challenge facing post-revolution Bangladesh: the gap between moral authority and administrative capacity.

Revolutions often remove old power structures quickly. Building lawful, neutral institutions takes much longer. When that gap is not managed carefully, society pays the price.

For citizens, the message was unsettling: political alignment still determines safety, and law remains uneven.

For international partners, the concern was deeper: whether Bangladesh’s transition could maintain stability without slipping into recurring street violence.

Why This Matters Beyond Bangladesh

What happened in Gopalganj is not unique to Bangladesh. Many post-revolution states face the same dilemma — how to govern inclusively after polarisation, how to enforce law without vengeance, and how to protect dissent without encouraging disorder.

Bangladesh’s experience offers a reminder: legitimacy without institutional discipline is fragile.

A government may be morally justified, internationally admired, and publicly supported — yet still fail if it cannot enforce the rule of law consistently and early.

A Moment of Reckoning

Gopalganj should have been a warning shot, not a tragedy.

If the interim leadership cannot manage predictable political tensions in sensitive regions, future confrontations may be even harder to contain. Stability cannot rest on curfews and condemnations alone. It requires preparation, neutrality, and the quiet, unglamorous work of governance.

The world is watching Bangladesh’s transition closely. Incidents like Gopalganj will shape whether that transition is remembered as a step toward democracy — or a missed opportunity where ideals outran institutions.